How Shopify reduced storefront response times with a rewrite

This post originally appeared on the Shopify Engineering blog on August 20, 2020.

In January 2019, we set out to rewrite the critical software that powers all online storefronts on Shopify’s platform to offer the fastest online shopping experience possible, entirely from scratch and without downtime.

The Storefront Renderer is a server-side application that loads a Shopify merchant's storefront Liquid theme, along with the data required to serve the request (for example product data, collection data, inventory information, and images), and returns the HTML response back to your browser. Shaving milliseconds off response time leads to big results for merchants on the platform as buyers increasingly expect pages to load quickly, and failing to deliver on performance can hinder sales, not to mention other important signals like SEO.

The previous storefront implementation‘s development, started over 15 years ago when Tobi launched Snowdevil, lived within Shopify’s Ruby on Rails monolith. Over the years, we realized that the “storefront” part of Shopify is quite different from the other parts of the monolith: it has much stricter performance requirements and can accept more complexity implementation-wise to improve performance, whereas other components (such as payment processing) need to favour correctness and readability.

In addition to this difference in paradigm, storefront requests progressively became slower to compute as we saw more storefront traffic on the platform. This performance decline led to a direct impact on our merchant storefronts’ performance, where time-to-first-byte metrics from Shopify servers slowly crept up as time went on.

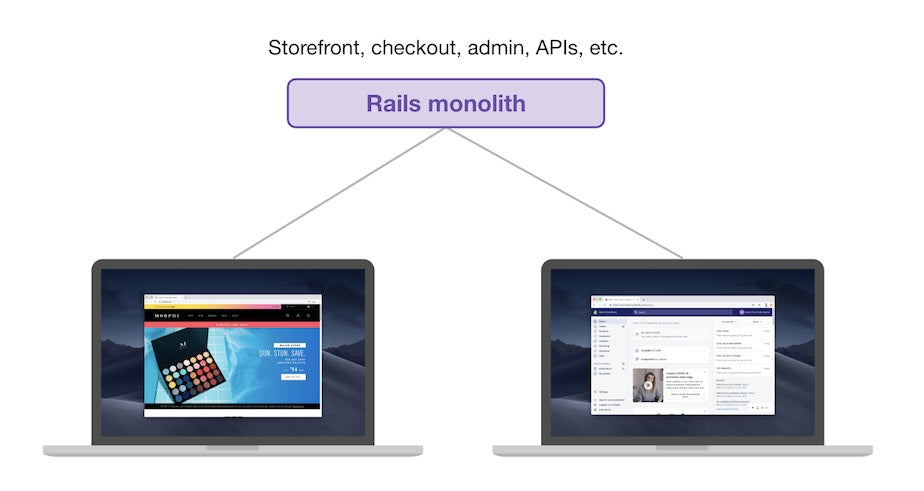

Here’s how the previous architecture looked:

Old Storefront Implementation

Before, the Rails monolith handled almost all kinds of traffic: checkout, admin, APIs, and storefront.

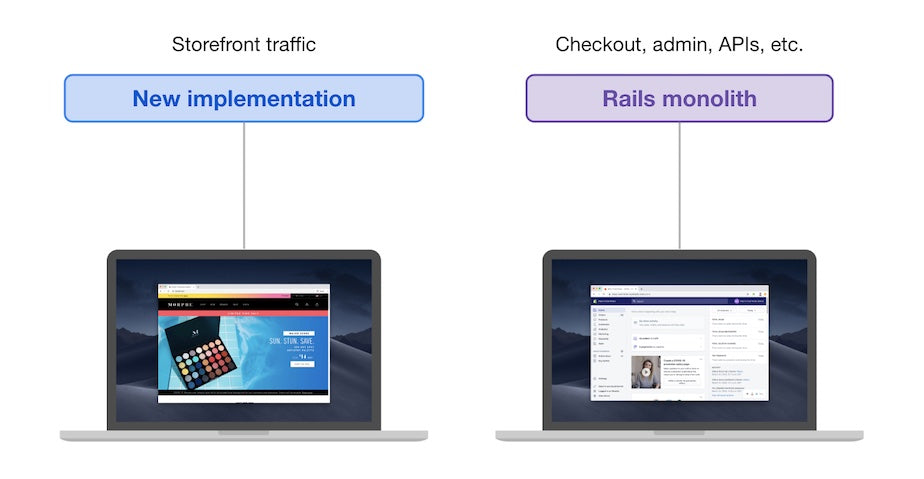

With the new implementation, traffic routing looks like this:

New Storefront Implementation

The Rails monolith still handles checkout, admin, and API traffic, but storefront traffic is handled by the new implementation.

Designing the new storefront implementation from the ground up allowed us to think about the guarantees we could provide: we took the opportunity of this evergreen project to set us up on strong primitives that can be extended in the future, which would have been much more difficult to retrofit in the legacy implementation. An example of these foundations is the decision to design the new implementation on top of an active-active replication setup. As a result, the new implementation always reads from dedicated read replicas, improving performance and reducing load on the primary writers.

Similarly, by rebuilding and extracting the storefront-related code in a dedicated application, we took the opportunity to think about building the best developer experience possible: great debugging tools, simple onboarding setup, welcoming documentation, and so on.

Finally, with improving performance as a priority, we work to increase resilience and capacity in high load scenarios (think flash sales: events where a large number of buyers suddenly start shopping on a specific online storefront), and invest in the future of storefront development at Shopify. The end result is a fast, resilient, single-purpose application that serves high-throughput online storefront traffic for merchants on the Shopify platform as quickly as possible.

Defining our success criteria

Once we clearly outlined the problem we’re trying to solve and scoped out the project, we defined three main success criteria:

- Establishing feature parity: for a given input, both implementations generate the same output.

- Improving performance: the new implementation runs on active-active replication setup and minimizes server response times.

- Improving resilience and capacity: in high-load scenarios, the new implementation generally sustains traffic without causing errors.

Building a verifier mechanism

Before building the new implementation, we needed a way to make sure that whatever we built would behave the same way as the existing implementation. So, we built a verifier mechanism that compares the output of both implementations and returns a positive or negative result depending on the outcome of the comparison.

This verification mechanism runs on storefront traffic in production, and it keeps track of verification results so we can identify differences in output that need fixing. Running the verifier mechanism on production traffic (in addition to comparing the implementations locally through a formal specification and a test suite) lets us identify the most impactful areas to work on when fixing issues, and keeps us focused on the prize: reaching feature parity as quickly as possible. It’s desirable for multiple reasons:

- giving us an idea of progress and spreading the risk over a large amount of time

- shortening the period of time that developers at Shopify work with two concurrent implementations at once

- providing value to Shopify merchants as soon as possible.

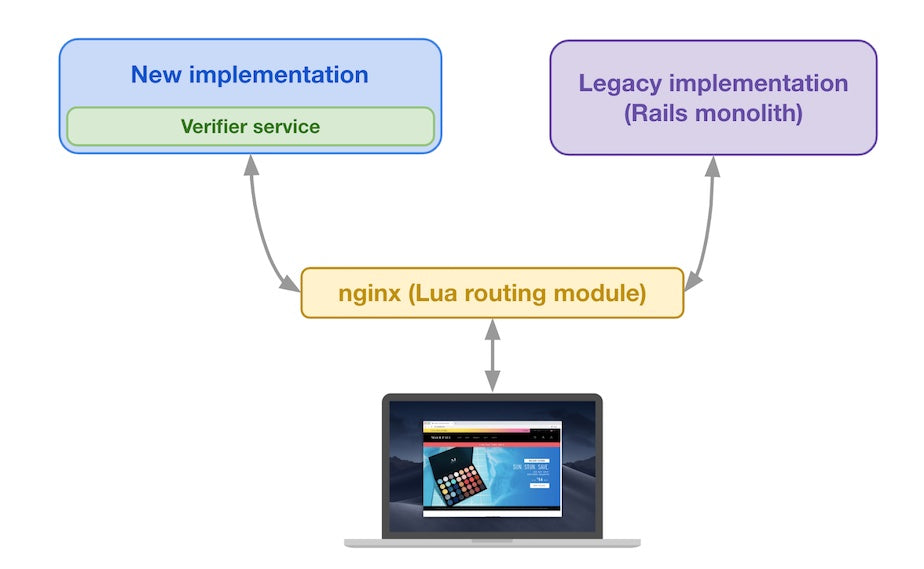

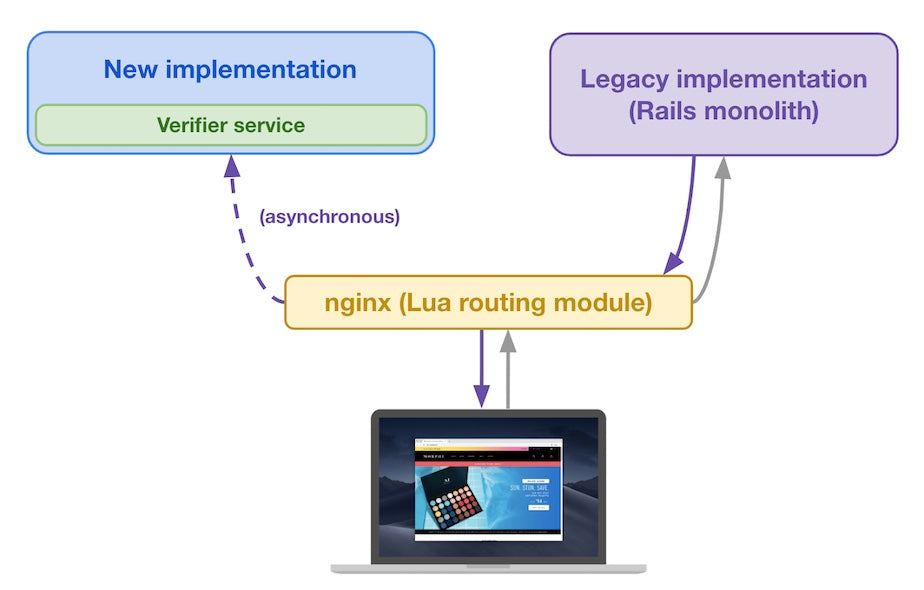

There are two parts to the entire verifier mechanism implementation:

- A verifier service (implemented in Ruby) compares the two responses we provide and returns a positive or negative result depending on the verification outcome. Similar to a `diff` tool, it lets us identify differences between the new and legacy implementations.

- A custom nginx routing module (implemented in Lua on top of OpenResty) sends a sample of production traffic to the verifier service for verification. This module acts as a router depending on the result of the verifications for subsequent requests.

The following diagram shows how each part interacts with the rest of the architecture:

Legacy implementation and new implementation at the same conceptual layer

The legacy implementation (the Rails monolith) still exists, and the new implementation (including the Verifier service) is introduced at the same conceptual layer. Both implementations are placed behind a custom routing module that decides where to route traffic based on the request attributes and the verification data for this request type. Let’s look at an example.

When a buyer’s device sends an initial request for a given storefront page (for example, a product page from shop XYZ), the request is sent to Shopify’s infrastructure, at which point an nginx instance handles it. The routing module considers the request attributes to determine if other shop XYZ product page requests have previously passed verification.

First request routed to Legacy implementation

Since this is the first request of this kind in our example, the routing module sends the request to the legacy implementation to get a baseline reference that it will use for subsequent shop XYZ product page requests.

Routing module sends original request and legacy implementation’s response to the new implementation

Once the response comes back from the legacy implementation, the Lua routing module sends that response to the buyer. In the background, the Lua routing module also sends both the original request and the legacy implementation’s response to the new implementation. The new implementation computes a response to the original request and feeds both its response and the forwarded legacy implementation’s response to the verifier service. This is done asynchronously to make sure we’re not adding latency to responses we send to buyers, who don’t notice anything different.

At this point, the verifier service received the responses from both the legacy and new implementations and is ready to compare them. Of course, the legacy implementation is assumed to be correct as it’s been running in production for years now (it acts as our reference point). We keep track of differences between the two implementations’ responses so we can debug and fix them later. The verifier service looks at both responses’ status code, headers, and body, ensuring they’re equivalent. This lets us identify any differences in the responses so we make sure our new implementation behaves like the legacy one.

Time-related and randomness-related exceptions make it impossible to have exactly byte-equal responses, so we ignore certain patterns in the verifier service to relax the equivalence criteria. The verifier service uses a fixed time value during the comparison process and sets any random values to a known value so we reliably compare the outputs containing time-based and randomness-based differences.

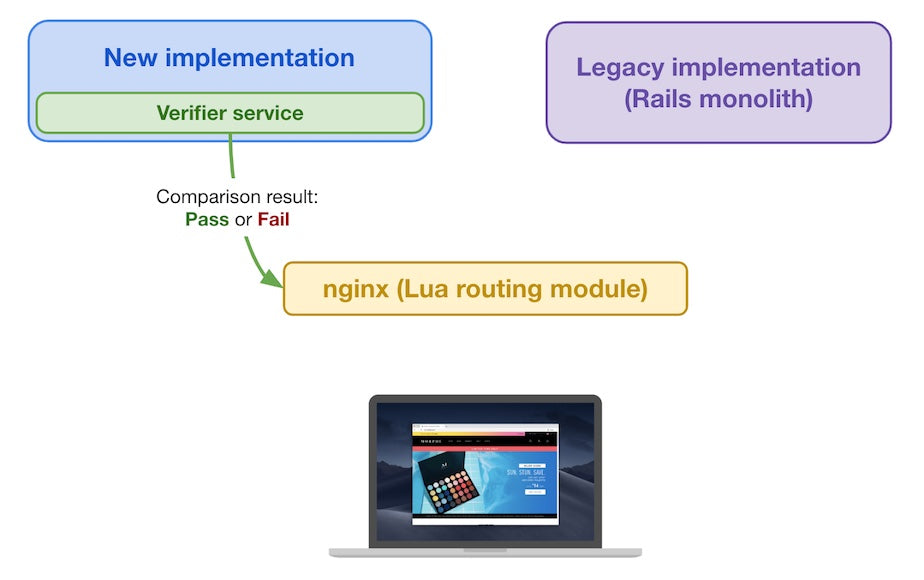

The verifier service sends comparison result back to the Lua module

The verifier service sends the outcome of the comparison back to the Lua module, which keeps track of that comparison outcome for subsequent requests of the same kind.

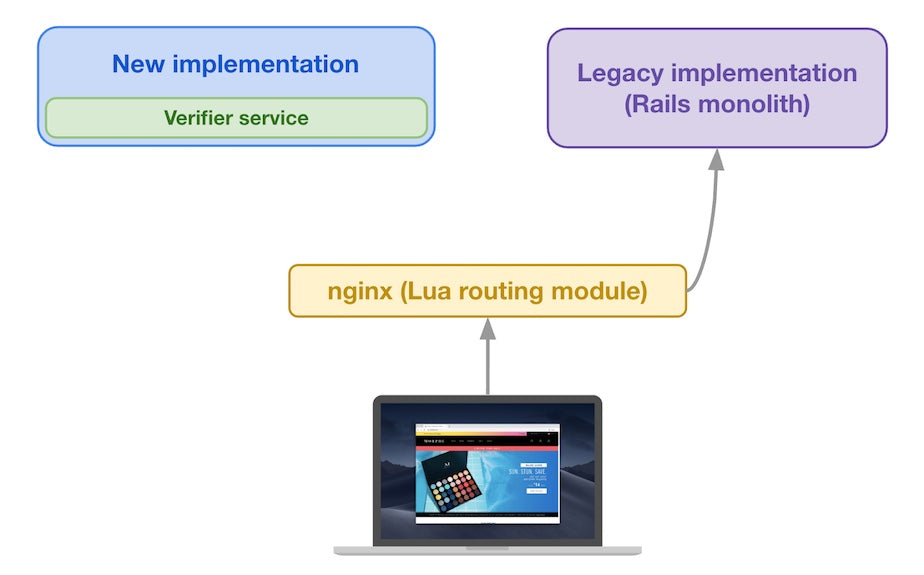

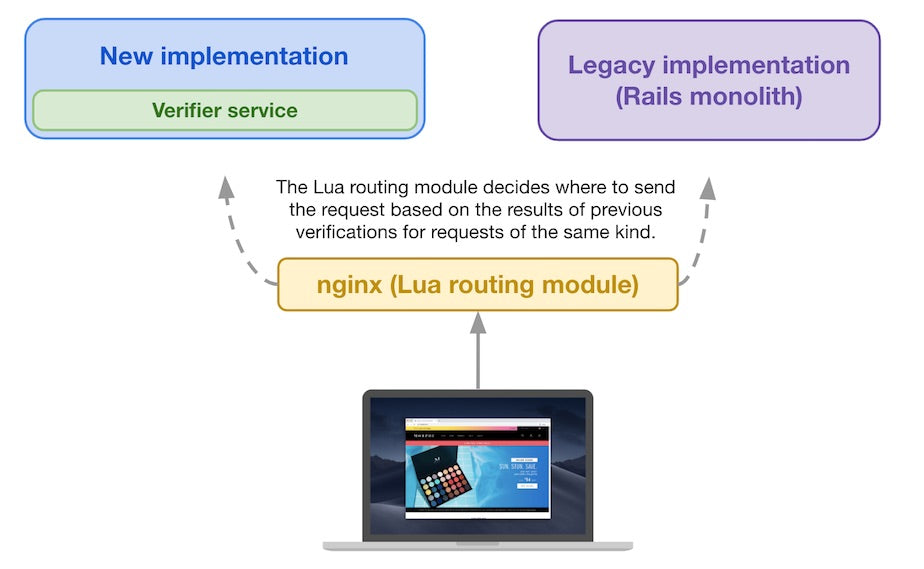

Dynamically routing requests to the new implementation

Once we had verified our new approach, we tested rendering a page using the new implementation instead of the legacy one. We iterated upon our verification mechanism to allow us to route traffic to the new implementation after a given number of successful verifications. Here’s how it works.

Just like when we only verified traffic, a request arrives from a client device and hits Shopify’s architecture. The request is sent to both implementations, and both outputs are forwarded to the verifier service for comparison. The comparison result is sent back to the Lua routing module, which keeps track of it for future requests.

When a subsequent storefront request arrives from a buyer and reaches the Lua routing module, it decides where to send it based on the previous verification results for requests similar to the current one (based on the request attributes

For subsequent storefront requests, the Lua routing module decides where to send it

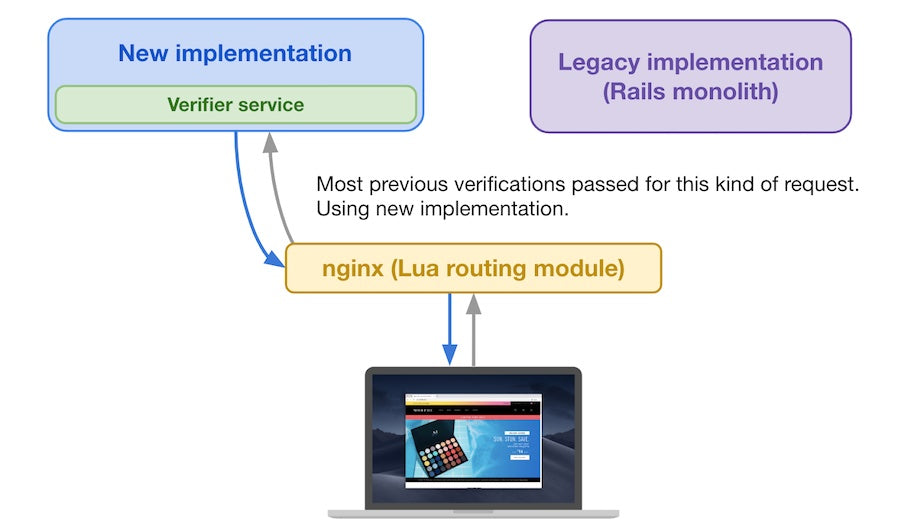

If the request was verified multiple times in the past, and nearly all outcomes from the verifier service were “Pass”, then we consider the request safe to be served by the new implementation.

If most verifier service results are “Pass”, then it uses the new implementation

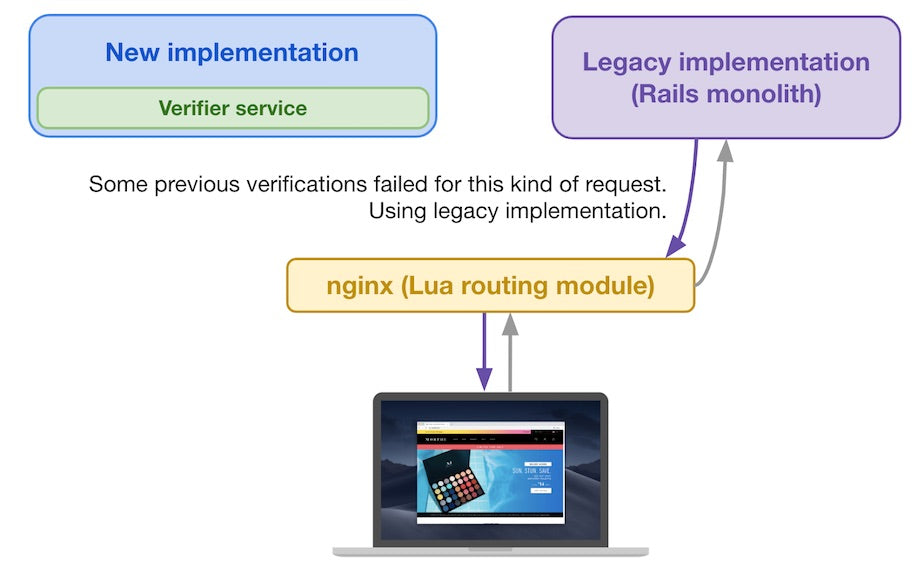

If, on the other hand, some verifications failed for this kind of request, we’ll play it safe and send the request to the legacy implementation.

If most verifier service results are “Fail”, then it uses the old implementation

Successfully Rendering In Production

With the verifier mechanism and the dynamic router in place, our first goal was to render one of the simplest storefront pages that exists on the Shopify platform: the password page that protects a storefront before the merchant makes it available to the public.

Once we reached full parity for a single shop’s password page, we tested our implementation in production (for the first time) by routing traffic for this password page to the new implementation for a couple of minutes to test it out.

Success! The new implementation worked in production. It was time to start implementing everything else.

Increasing feature parity

After our success with the password page, we tackled the most frequently accessed storefront pages on the platform (product pages, collection pages, etc). Diff by diff, endpoint by endpoint, we slowly increased the parity rate between the legacy and new implementations.

Having both implementations running at the same time gave us a safety net to work with so that if we introduced a regression, requests would easily be routed to the legacy implementation instead. Conversely, whenever we shipped a change to the new implementation that would fix a gap in feature parity, the verifier service starts to report verification successes, and our custom routing module in nginx automatically starts sending traffic to the new implementation after a predetermined time threshold.

Defining “good” performance with Apdex scores

We collected Apdex (Application Performance Index) scores on server-side processing time for both the new and legacy implementations to compare them.

To calculate Apdex scores, we defined a parameter for a satisfactory threshold response time (this is the Apdex’s “T” parameter). Our threshold response time to define a frustrating experience would then be “above 4T” (defined by Apdex).

We defined our “T” parameter as 200ms, which lines up with Google’s PageSpeed Insights recommendation for server response times. We consider server processing time below 200ms as satisfying and a server processing time of 800ms or more as frustrating. Anything in between is tolerated.

From there, calculating the Apdex score for a given implementation consists of setting a time frame, and counting three values:

- n, the total number of responses in the defined time frame

- s, the number of satisfying responses (faster than 200ms) in the time frame

- t, the number of tolerated responses (between 200ms and 800ms) in the time frame

Then, we calculate the Apdex score:

apdexScore = (s + t/2) / n

By calculating Apdex scores for both the legacy and new implementations using the same t parameter, we had common ground to compare their performance.

Methods to improve server-side storefront performance

We want all Shopify storefronts to be fast, and this new implementation aims to speed up what a performance-conscious theme developer can’t by optimizing data access patterns, reducing memory allocations, and implementing efficient caching layers.

Optimizing data access patterns

The new implementation uses optimized, handcrafted SQL multi-select statements maximizing the amount of data transferred in a single round trip. We carefully vet what we eager-load depending on the type of request and we optimize towards reducing instances of N+1 queries.

Reducing memory allocations

We reduce the number of memory allocations as much as possible so Ruby spends less time in garbage collection. We use methods that apply modifications in place (such as #map!) rather than those that allocate more memory space (like #map). This kind of performance-oriented Ruby paradigm sometimes leads to code that’s not as simple as idiomatic Ruby, but paired with proper testing and verification, this tradeoff provides big performance gains. It may not seem like much, but those memory allocations add up quickly, and considering the amount of storefront traffic Shopify handles, every optimization counts.

Implementing efficient caching layers

We implemented various layers of caching throughout the application to reduce expensive calls. Frequent database queries are partitioned and cached to optimize for subsequent reads in a key-value store, and in the case of extremely frequent queries, those are cached directly in application memory to reduce I/O latency. Finally, the results of full page renders are cached too, so we can simply serve a full HTTP response directly from cache if possible.

Measuring performance improvement successes

Once we could measure the performance of both implementations and reach a high enough level of verified feature parity, we started migrating merchant shops. Here are some of the improvements we’re seeing with our new implementation:

- Across all shops, average server response times for requests served by the new implementation are 4x to 6x faster than the legacy implementation. This is huge!

- When migrating a storefront to the new implementation, we see that the Apdex score for server-side processing time improves by +0.11 on average.

- When only considering cache misses (requests that can’t be served directly from the cache and need to be computed from scratch), the new implementation increases the Apdex score for server-side processing time by a full +0.20 on average compared to the previous implementation.

- We heard back from merchants mentioning a 500ms improvement in time-to-first-byte metrics when the new implementation was rolled out to their storefront.

So another success! We improved store performance in production.

Now how do we make sure this translates to our third success criteria?

Improving sesilience and capacity

While working on the new implementation, the Verifier service identified potential parity gaps, which helped tremendously. However, a few times we shipped code to production that broke in exceedingly rare edge cases that it couldn’t catch.

As a safety mechanism, we made it so that whenever the new implementation would fail to successfully render a given request, we’d fall back to the legacy implementation. The response would be slower, but at least it was working properly. We used circuit breakers in our custom nginx routing module so that we’d open the circuit and start sending traffic to the legacy implementation if the new implementation was having trouble responding successfully. Read more on tuning circuit breakers in this blog post by my teammate Damian Polan.

Increase capacity in high-load scenarios

To ensure that the new implementation responds well to flash sales, we implemented and tweaked two mechanisms. The first one is an automatic scaling mechanism that adds or remove computing capacity in response to the amount of load on the current swarm of computers that serve traffic. If load increases as a result of an increase in traffic, the autoscaler will detect this increase and start provisioning more compute capacity to handle it.

Additionally, we introduced in-memory cache to reduce load on external data stores for storefronts that put a lot of pressure on the platform’s resources. This provides a buffer that reduces load on very-high traffic shops.

Failing fast

When an external data store isn’t available, we don’t want to serve buyers an error page. If possible, we’ll try to gracefully fall back to a safe way to serve the request. It may not be as fast, or as complete as a normal, healthy response, but it’s definitely better than serving a sad error page.

We implemented circuit breakers on external datastores using Semian, a Shopify-developed Ruby gem that controls access to slow or unresponsive external services, avoiding cascading failures and making the new implementation more resilient to failure.

Similarly, if a cache store isn’t available, we’ll quickly consider the timeout as a cache miss, so instead of failing the entire request because the cache store wasn’t available, we’ll simply fetch the data from the canonical data store instead. It may take longer, but at least there’s a successful response to serve back to the buyer.

Testing failure scenarios and the limits of the new implementation

Finally, as a way to identify potential resilience issues, the new implementation uses Toxiproxy to generate test cases where various resources are made available or not, on demand, to generate problematic scenarios.

As we put these resilience and capacity mechanisms in place, we regularly ran load tests using internal tooling to see how the new implementation behaves in the face of a large amount of traffic. As time went on, we increased the new implementation’s resilience and capacity significantly, removing errors and exceptions almost completely even in high-load scenarios. With BFCM 2020 coming soon (which we consider as an organic, large-scale load test), we’re excited to see how the new implementation behaves.

Where we’re at currently

We’re currently in the process of rolling out the new implementation to all online storefronts on the platform. This process happens automatically, without the need for any intervention from Shopify merchants. While we do this, we’re adding more features to the new implementation to bring it to full parity with the legacy implementation. The new implementation is currently at 90%+ feature parity with the legacy one, and we’re increasing that figure every day with the goal of reaching 100% parity to retire the legacy implementation.

As we roll out the new implementation to storefronts we are continuing to see and measure performance improvements as well. On average, server response times for the new implementation are 4x faster than the legacy implementation. Rhone Apparel, a Shopify Plus merchant, started using the new implementation in April 2020 and saw dramatic improvements in server-side performance over the previous month.

We learned a lot during the process of rewriting this critical piece of software. The strong foundations of this new implementation make it possible to deploy it around the world, closer to buyers everywhere, to reduce network latency involved in cross-continental networking, and we continue to explore ways to make it even faster while providing the best developer experience possible to set us up for the future.

This blog post is not available under a Creative Commons license.