Inspecting a “USB Drop” Attack Using olevba.py

TL;DR: Never plug USB keys you find laying around in your computer. They may contain malware that silently deploys as you plug it in, stealing sensitive information and downloading viruses in the background.

For those of you who may know me, I’m the kind of guy who runs Linux on his computer full-time (except for the occasional music production or video editing session). This means no Windows vulnerability to worry about, no random update that starts while I’m working… and also no Microsoft Office suite. This is important to the story, so keep it in mind.

It all started with a regular old bright orange USB key that was left laying around on a meeting room table.

The key itself wasn’t identified and did not appear to give away any information

about its owner, so I thought I would just do my good deed of the day and try to

find some sort of IF_FOUND.txt file to identify its owner and give it back

to them. So I proceeded to boot up my Linux partition (you can never be too

cautious!), then plugged in the key.

At first glance, the key contained seemingly important (and sensitive!) information about the company’s assets and strategic planning. I first wondered why anyone would think it safe to carry such valuable documents on a friggin’ unencrypted USB key (and most importantly, forgetting it in a meeting room). Then, in my attempt to identify the owner of the key, I opened a random folder and started browsing through the files.

A few seconds in, two oddidities made me realize that something wasn’t quite right.

First, all the documents on the key had the .docm extension, which are files

known as “Office Word Documents with Macros”, basically meaning that they’re

Word documents with Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) code baked in. In Excel

spreadsheets and Access databases especially, VBA Macros allow for improved

functionality and useful sequences of actions that can be used to automate

otherwise mundane tasks.

The other thing that ticked me off was the Date modified attribute of the files on the key: they were all set to the exact same date. I mean, yes, the files could all have been copied together and their Date modified fields resetted to the same moment, but still. It just didn’t feel right.

The combination of the way the key was left on the table AND the two oddities I found led me to think about a completely different scenario:

This wasn’t a regular old “normal” USB key. Somebody was trying to fool me, and I needed to delve deeper.

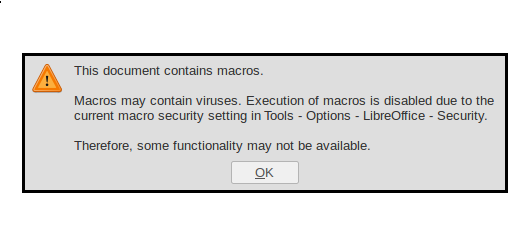

I took the risk of opening one of the Word documents using LibreOffice (with macros disabled, of course), but was left disappointed when I saw that the document was completely empty. I tried opening another file, hoping to see something in there, but alas, it was completely empty as well.

The rabbit hole was deepening yet again.

Thinking about the .docm extension, I quickly understood that the documents

probably contained malicious VBA code, but I did not know exactly what kind of

stuff I was dealing with. I figured I would just keep digging until I would find

something. After a quick Google search, I stumbled upon the excellent

olevba.py tool, part of the

oletools collection, which parses

MS Office documents to detect VBA macros then extract their source code.

Starting with MS Office 2007, Word documents are really just OpenXML files

wrapped in .doc/.docm/ .docx extensions, so after extracting one of the

documents and browsing through the extracted files, I found an interesting

binary file which was significantly larger than the others, appropriately named

vbaProject.bin. I was pretty confident that this was the file that contained

malicious VBA code, probably downloading malware from a remote server and

executing it on the victim’s machine (in this case, my computer, but since I was

not on Windows, the chances of being attacked were pretty slim).

However, extracting the source of the vbaProject.bin file using the

olevba.py tool gave me a completely different answer:

Huh. So this was not malware, after all. This Word document was simply sending the hostname and username to a remote server to identify who had plugged in the rogue USB key and opened one of its files. I then realized that this was an infosec effort to identify imprudent employees who used the (intentionally left behind) USB keys (and who should never do that, unless they absolutely know and trust the USB key).

I was pleasantly surprised to see that the subroutine actually used MsgBox to

create a popup announcing to the imprudent user that “the file is corrupted and

cannot be opened”.

Long story short: only use USB keys you know and trust.